On September 23rd, the Council of the European Union presented the "New Pact on Migration and Asylum" to the public. The pact focuses largely on migration controls at the European Union's external borders. Recent developments in the Mediterranean Sea show that refugees and migrants already face extreme challenges in reaching EU borders.

Hardly any asylum-seekers arrived in Europe at the height of the Corona pandemic in April: registered were only 78 in Greece, 500 in Spain, and fewer than 700 in Italy. Numbers increased over the following months, but at a relatively low level. A look at the three main Mediterranean escape routes shows that Corona was not the reason. Rather, the culprit was strict and often illegal border controls in Turkey, Libya, and Europe.

Eastern Mediterranean Route (Turkey-Greece)

At the border

Most asylum-seekers and refugees along the Eastern Mediterranean route are picked up by the Turkish coast guard and brought back to Turkey. Fewer than half who attempt the journey reach the Greek islands. These are mainly Afghans (about 40 percent) and Syrians (about 25 percent).Quelle

Many asylum-seekers are also rejected by the Greek coast guard (so-called pushbacks). According to a New York Times investigative report, the Greek coast guard has released more than 1,000 asylum-seekers in inflatable boats on the high seas. The UNHCR has denounced this practice because it violates the "non-refoulement" principle of the Geneva Refugee Conventions well as the European Convention on Human Rights.

In March 2020, the Greek government decided to stop accepting asylum applications for one month. An additional one-month halt on applications followed in May. Athens has also announced further measures to reduce irregular migration: they plan to erect a 2.7 kilometer long floating barrier off the island of Lesbos.

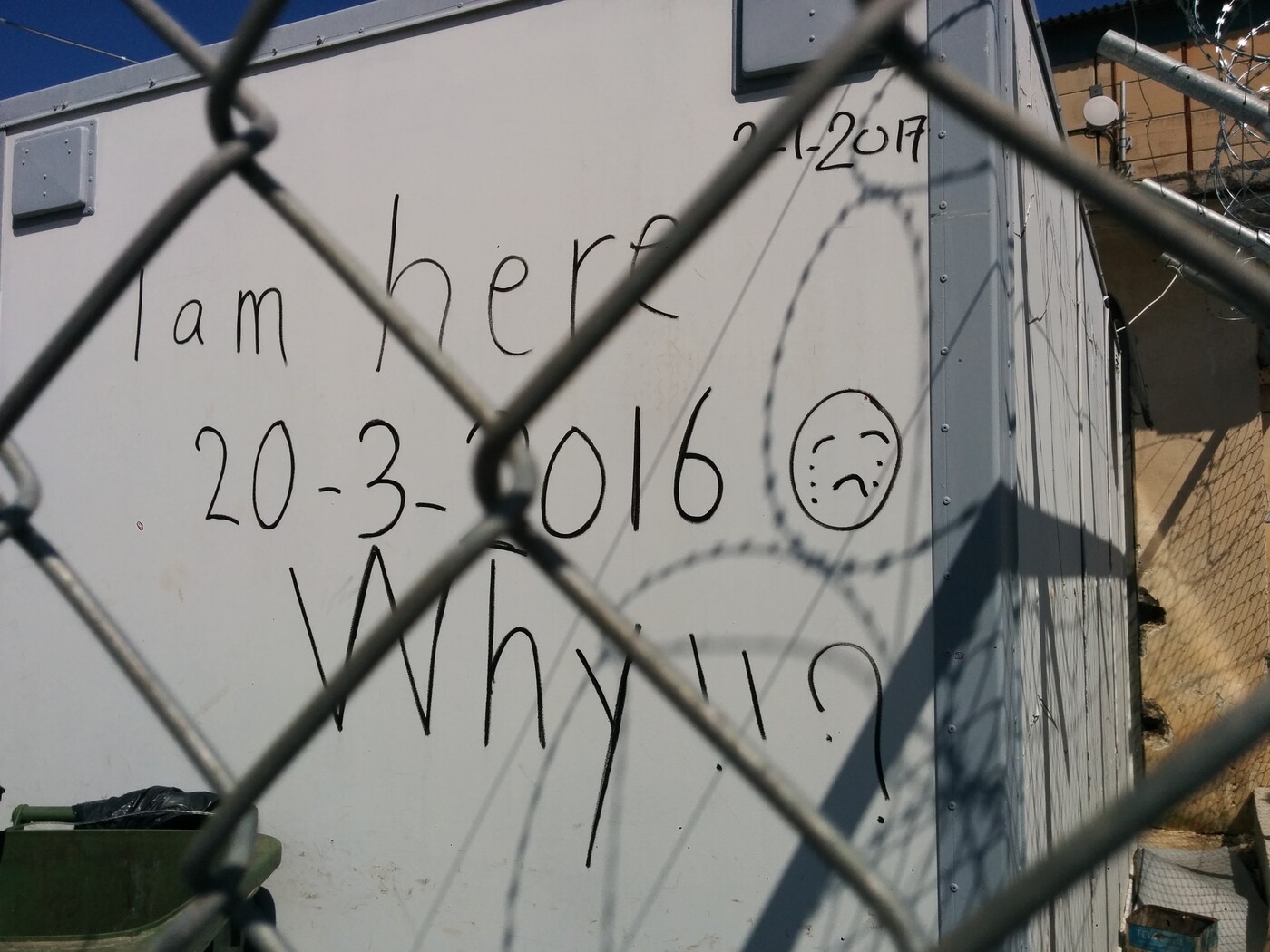

The Hotspot Approach

In 2019, the number of refugees at so-called hotspots on Greek islands increased significantly. Slums have formed around reception facilities on the islands, where violence and disease are widespread. Reception facilities have also become targets of right-wing extremist violence. In March 2020, the Greek government started to transfer more people from the islands to the mainland. About 240 unaccompanied minors were distributed from the Greek islands to seven EU member states . Germany has announced that it will accept an additional 294 sick children and their families. Yet, facilities remain extremely overcrowded, and refugees are only allowed to leave under certain conditions because of preventive measures against COVID-19.

Central Mediterranean Route (North Africa-Italy/Malta)

At the border

The number of people crossing the Central Mediterranean to Italy and Malta decreased in 2019. This was partly due to the fact that a large number of migrants at sea were picked up by the Libyan coast guard. The numbers of those arriving to Europe via the Central Mediterranean began to rise again in the summer of 2020.

One reason: More people are coming from Tunisia. About 40 percent of the people who reached Italy in 2020 were Tunisian (as of July 31, 2020). Since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic - and the subsequent collapse of the tourism industry - the country has been in a deep economic crisis. Many people are trying to get to Europe, both unemployed Tunisians and many of the approximately 75,000 migrants in the country.

Currently, two sea rescue ships - the "Sea Watch 4" and the "Louise Michel" - patrol the Central Mediterranean Sea. Several sea rescue boats have been confiscated in Italy, allegedly because of technical defects. The EU mission "Irini", successor of the "Sophia" mission, is only partially involved in rescue operations. It is primarily concerned with combating arms smuggling.

The Central Mediterranean route is still the most dangerous route in the Mediterranean. Since early 2020, the International Organization for Migration has documented 359 deaths on the route. The exact number of victims is unknown. The number of deaths has more than halved compared to the previous year.Quelle

The Hotspot Approach

Ships with asylum-seekers on board have difficulty finding a "safe haven" in Italy and Malta. Even before the pandemic, ships with hundreds of people on board had to wait multiple weeks before being allowed ashore.

Currently, asylum-seekers arriving in Italy must first remain on a quarantine ship or in closed quarantine facilities in Sicily. According to the Italian Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration (ASGI), the living conditions in these closed facilities are very stressful for refugees. Hundreds of refugees have broken out of two hotspots in Sicily.

Western Mediterranean Route (Northwest Africa - Spain)

At the border

The Western Mediterranean route became the main route to Europe in 2018, but significantly fewer people are arriving to Spain via the route today. One reason for this is that Spain and Morocco signed an agreement in February 2019 to manage irregular migration. According to the agreement, asylum-seekers at sea who are rescued in joint operations by Spanish and Moroccan forces are returned to Morocco. Also at play are stricter border controls due to the Covid-19 pandemic, as the Alarm Phone Initiative recently reported. The Moroccan border authorities are said to have arrested many protection seekers - especially in the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla. The Spanish "Guardia Civil" has also increased border controls.

At the same time, more people from West Africa are trying to reach the Canary Islands: Just over 500 people came to Spain via the so-called "Atlantic route" between January and August 2019, compared to over 4,000 between January and August 2020 (as of August 30, 2020). Difficult and unpredictable weather conditions in the Atlantic make this route particularly dangerous.Quelle

The Hotspot Approach

There are no hotspots in Spain. Arriving asylum-seekers are examined by doctors from the Spanish Red Cross and then registered in police facilities. The next step is accommodation in primary reception centers (Centros de acogida de refugiados, CAR). Yet, the accommodation can only hold slightly more than 400 places (as of August 2020). As a result, many have to be cared for by NGOs - or end up homeless.Quelle

By Fabio Ghelli, translation by Sophia Burton